A range of resources, including insights documents, were developed to support the four regional Hui Whakaoranga and virtual Hui Whakaoranga in 2021. These initial resources provided further context to and expert perspectives on the theme of Hui Whakaoranga 2021, ‘Whāia te Pae Ora mō ngā mokopuna – Securing wellbeing for the next generation’.

View the full summary report of Hui Whakaoranga 2021.

Additional resources were also created for anyone else interested in Hui Whakaoranga and our collective journey towards Pae Ora – healthy futures for Māori.These resources capture kōrero shared at each hui and include highlights videos, recordings of the keynote speakers and illustrations developed by the League of Live Illustrators.

These resources are available below.

On this page:

Keynotes videos

Watch the recordings of our keynote speakers Tā Mason Durie and Dr Ashley Bloomfield.

Auē te rā, te tai rā, te tai rā, e pari ana te tai ki hea?

E pari ana te tai ki te kauheke kaumātua.

He atua, he atua!

Tēnā ngā reo o ngā kārangatanga maha, koutou o te kāinga.

John, tēnā koutou, nā koutou te reo pōhiri, te reo karanga, ā, kua tae mai te katoa ki te āta tirotiro i ngā tini take e pā ana ki a tātou.

Thank you for the introduction.

Little bit longer than necessary but thank you for it.

So I'm going to talk a bit about health.

Just want to clarify when I talk about health, I'm not talking about sickness.

Sometimes that word gets confused.

When we say health, we talk about sickness.

Health services are sickness services.

I want to talk about health.

If we're going to go anywhere into the future, we need to put health first, not start with sickness.

Now, I've forgotten what I was going to talk about.

[Laughter]

Facilitator: What I do want to emphasise is that we can't just blindly walk into the future.

There is a past that really constructs the future.

If we get to know what's been important in the past, we know what to build on as we move into the future.

So I'm actually much better at looking into the past and I'm a little bit scared about looking into the future.

But the past is, to some extent, captured in five decades that I thought we might look at.

Go back to 1970.

Some of you won't remember 1970 because you weren’t born.

Others, you will have forgotten it because you can't remember.

[Laughs].

But to look at decade one, which was 1970 to 1979.

Decade two, up to 1980 to '89.

Decade three, 1990 to 1999.

2000 to 2009, and the decade that we've just left a year or two ago, 2010 to 2019.

So what I want to talk about is some of the events that helped shaped where we are today that happened in those decades.

I'm talking about events that sort of have some personal connection to me or things that I know about.

But there will be many, many other events that I won't be talking about that have helped shaped where we are today and will shape our path into tomorrow.

So before I do that, I just want to do a quick step back into the 1960s.

When I was at medical school in the 1960s, these were medical students whom I knew and who became doctors and were part and parcel of the journey that I've been on.

Unfortunately all of these have passed on.

But I remember them as colleagues and the important contributions that all of them made to where we are today.

So decade one then, 1970.

That's the year I came back from study in Canada, in Montreal, to take a position as a psychiatrist in Manawaroa.

Manawaroa was a psychiatrist unit that had just been opened.

They opened it the week before I got back as a community mental health facility.

There were two of them in the country at the same time had been built, one at Palmerston North, one at Invercargill.

The idea was that these facilities would be more linked to the community than they were previously when mental hospitals used to be the only source of support.

In 1972 there was an act passed which shut down the mental hospitals and transferred the responsibilities for mental health to hospital boards and later on to district hospital boards.

So some of you will remember those hospitals.

The last one to close down was Lake Alice which didn’t close down until 1999 and that was because it had the maximum-security unit within it and they had a hard job knowing what to do with that.

But these were huge hospitals they'd opened in the 1860s.

Some of them had 2000 patients.

Smaller ones had 800 patients.

But they were all major institutions and that was the centre for mental health in those days.

So in 1970, then that began to change.

Other really important things happened in 1970 as well.

1972 a group of Māori students at Auckland University formed Ngā Tamatoa.

They took a march - a petition - to Wellington to say that te reo Māori should be part and parcel of our education and of all our programs in the country.

1975, Dame Whina Cooper led a land march from far north down to parliament under the catch cry not one acre more.

That was a petition which said that Māori land should be owned by Māori.

[Aside discussion] Facilitator: So Whina Cooper's march then in 1975, joined by thousands of others who all came down to protest the way that Māori land was being alienated and the need for Māori land to stay with Māori.

Two years after that, the Waitangi Tribunal was formed.

Partly as a response to the land march but partly also because of the numerous complaints that had been made to government without any way of solving them and it was Mat Rata who introduced the notion for and supported the passage of the Waitangi Tribunal Act.

1977, Bastion Point.

Where Ngāti Whātua, then joined by hundreds of others from all around the country, took possession of their land which Muldoon was about to sell off to build high rise homes.

That didn’t happen.

It didn’t happen because of Bastion Point and the fight that those people put to protect their own land.

In 1978, the Raglan golf course occupation occurred.

A similar effort.

The golf course had been built on land which had never been formally sold to them.

It had been alienated from the people there.

So in decade one, some big changes going on.

Mental health changing.

Big emphasis on te reo Māori.

Big emphasis on land.

Land has been a fairly critical component of health.

Moving on then to decade two, between 1980 and 1989.

1981, the first kōhanga reo was opened.

Ground-breaking.

A lot of criticism of it.

Also a lot of support.

1983, the Māori staff at the Tokanui Hospital opened Whaiora which was the first Māori - kaupapa Māori health unit within a hospital.

1993, the Māori nurses formed the Kaunihera o Ngā Neehi Māori.

Still in existence.

They had come together as a group.

In 1994 there was a big hui, the Hui Taumata, which looked at the Māori economy.

In that same year, the Māori Women's Welfare League published Rapuora which was a book, contained their findings from a research project they had done on the health of Māori women.

It was done by the League themselves.

All the interviews were done by League members, average about 65, 66.

These were women who had not had any experience of researching.

Would knock on the door, is there a Māori woman in this house?

If they said yes, then they went in and interviewed that woman.

They had 92 per cent acceptance.

That's because when they knocked on the door, they also put their foot in the door to make sure that they got in.

They had their own way of interviewing too, some of these women.

One of the questions was what is your religion?

I think if you put that in a questionnaire now, not many people would understand what you mean.

But in those days, a very important issue.

In the feedback that I heard from one of the ladies who had done the interviewing, she said this woman said to her, I'm an atheist, I don’t have a religion.

So the interviewer got up and said my dear, your grandmother was an Anglican, your mother is an Anglican, so you're an Anglican.

[Laughter] Facilitator: She ticked the Anglican box.

So the quality of the research sometimes came under criticism but the findings of the research were incredibly important and it represented a whole new approach to research and a much better understanding of the wider capacities of health of women that but of Māori generally.

1984, the Whānau o Waipareira was formally operated as a trust.

In 1985, the first kura kaupapa Māori opened at the Hoani Waititi Marae.

1987, the Māori Language Act was passed and in 1988, te Pūao-te-ata-tū and Mātua Whāngai were produced as really important documents.

Mātua Whāngai was an answer to Oranga Tamariki.

The idea was that there would be no children in placement.

They would be placed with whānau.

It worked for a time and then it was taken back to the more conventional approach that operated.

So in that decade, 1980 to 1989, some amazing changes.

The other thing that happened, and John already referred to this this morning, was the Hui Whakaoranga in 1984, held at the Hoani Waititi Marae in Auckland.

Had been organised through the Department of Health and Lorna Dyall and Paratene Ngata had a large role in putting it all together.

Attended by a whole range of people.

Some involved in the health services.

Some involved in iwi development.

Some involved in New Zealand Māori Council.

A whole range of people who are not just involved directly in health.

We had some great speakers there.

There were these five particularly that I - Dame Whina Cooper came onto the marae waving a karamū branch.

Throughout the hui, she said this is the answer.

She has convinced that karamū, and what she was saying of course, was the wider environment is a really important part of health.

She stayed with the hui right through.

She was a bit older then.

But Raiha Mahuta gave an address and she talked about Raukura Hauora o Tainui and that was the first Māori KMO.

The first Māori health organisation.

It had opened in 1983 and Raiha was involved in its opening.

People were in disbelief and thought that that will never work.

That you've got to be linked more closely to a medical situation to run a health service.

Raiha was showing that it doesn’t have to be that way and that was a foundational movement.

As I mentioned, the Māori Nursing Council had been established the year before.

They were in force at this hui.

Presented themselves.

Illustrated their own organisation, how they'd organised it, and that was a trail blazer.

[Willy Kaa] who was in education at that point gave a really inspiring address where he talked about the significance of education for health.

That was a fundamental on it.

Then Eru Pōmare talked a bit about his work he'd been doing on Māori and non-Māori health disparities.

So that was happening at this hui in 1984.

Then I was on a panel with three others.

Rose Pere was one of the panel members and she talked about Te Wheke, a model for health.

I talked about Whare Tapa Whā which had only been around for a couple of years.

Then Sonny Waru from Taranaki talked about a program he had established for glue sniffers.

I don’t think they have them now but back in those days glue sniffers used to be in the streets of Auckland.

He would take them back, up to 10 at a time, and they would a six week tour of the marae in Taranaki, staying on each one for a period of a week or 10 days.

At no stage did he talk about glue sniffing or being bad, he just gave them a strong feeling that they were part of a wider environment.

Again, that's lack for funding but what he was showing was that promoting the - helping people reach their potential and helping people focus on something positive is probably as important as addressing the problem.

Then Nitama Paewai, Doctor Paewai, who was a general practitioner at Kaitaia or Kawakawa.

Kaikohe was it?

Yeah.

He was a general practitioner there.

His family are here today, some of them.

He talked about how in addition to his work as a general practitioner, at nights he used to hold wananga or learning sessions for some of his whānau who felt - who were not very good at organising themselves financially.

So we had financial learning and economic planning for these whānau.

So they were some of the events that began to unfold at the Hui Whakaoranga.

There's one other really important event that happened.

That was through Whatarangi Winiata who was at the hui.

He got up and made a speech addressing the Health Department people who were there and finished up his speech by saying give us the money and we'll do the job.

That was his - and of course, that's been a cry ever since.

Give us the money and we'll do the job.

Decade three, 1990 to 1999.

1990, the Māori Congress was formed.

Officially formed.

It had started the year before.

[Unclear] and a Ratana leader, they sponsored it.

It really was an opportunity for iwi to get together without being funded by government, it was an iwi one.

Every year we put in a certain amount.

I think it was $5000.

Ngāti Kauwhata had always said well we are actually quite different from Ngāti Raukawa.

Until we heard that it was $5000 and we said actually, we are part of Raukawa through a different line.

[Laughter] Facilitator: So there was a bit of innovation going on that hui.

But they were quite powerful hui where iwi leaders were talking.

It came to an end in 1995.

One of the reasons, to me it was the main reason, was that there was a vote about Sealord's.

Some of you may remember the Sealord's debate that went on.

Is this a good deal we should accept?

It was a proposal for Māori fishing.

Or should we look at another proposal?

It was pretty clear that the congress leaders were fairly divided on it.

When they took the vote and the deal was approved, things began to fall apart.

Yet, the main theme for the hui had been kotahitanga.

Looking back on it - I was Secretary - missed an opportunity.

Really, what we should have done was not have a vote.

If the value you put most high is kotahitanga and you're going to vote on something that will divide you, you're going against your own values.

Don't vote.

What we should have done if we were going to vote was to have a vote to say that we recognise the independence of every iwi to make their own decisions on matters in their own rohe.

Really then, that focuses more on the kotahitanga than on voting.

So sometimes this vote of the majority rules is not actually a very fair or a very wise vote to have.

1993, the Electoral Reform Act was passed which clarified the position of Māori voters.

1995, the first Treaty settlements, Tainui Ngāi Tahu.

Both of them signed off.

I think there was 185 each for there and they became the standard for the settlement process which was to follow.

1995, the Pākaitore protest of Wanganui where iwi from Wanganui occupied the land known as Pākaitore.

That decade also saw the expansion of Māori health organisations.

From 1993.

That's when there was a health reform and the health reform separated the funders of health services from the providers of health services.

That enabled Māori organisations to apply for funding to the funder, not to a health service.

Today - that disappeared when the split between funder and provider came to an end.

So DHBs became the main funders and the main providers.

So I think you call that a conflict of interest.

But what gave birth to so many Māori organisations in those early years in the 1990s was it became possible to apply for funding from an independent funder rather than from a competitor.

So the number of KMOs, kaupapa Māori organisations, has blossomed ever since then.

But it started of course with the one in Tainui that I've spoken about already.

In that same time, the Māori health workforce began to expand.

It had been slow but then the number of doctors involved began to increase and in 1995 they formed themselves into an organisation called Te ORA.

Te ORA.

Te Ao Mārama, my psychologist I think - no.

Dentist.

Dentist and associated dental workers formed Te Ao Mārama.

Nga Pumanawa Hauora, research centres that were jointly funded.

So we began to see in the 1990s, a more definite entry into the workforce of Māori providers.

But in that, 1994, was also another hui.

The Te Ara Ahu Whakamua, the Māori Health Decade hui.

Ten years after the hui Whakaoranga.

They wanted to see a much stronger case for having accessible, better resourced, and accountable to Māori organisations.

They placed emphasis on whānau, but also on iwi, on wananga, and health clinics within the community.

They said that particular hui, that there was support for the establishment of a Māori health authority.

So here we are some years later, still trying to implement that.

Decade four, 2000 to 2009.

He Korowai Oranga, the Māori Health Strategy was emerged in 2002.

Te Rau Matatini, which become Te Rau Ora in 2002 also.

There was a foreshore and seabed procession which was really demanding Māori ownership of the foreshore and seabed rather than what had been proposed.

In 2005, the first Iwi Chairs Forum was held at the Takahanga Marae.

2006, Tuheitia became the sixth Māori king.

In 2007, Hauora Māori Standards of Health, the fourth edition appeared as did a framework for Māori health and addiction in 2008.

In 2009, there was a very significant Māori housing forum held.

Two other big events in that decade.

One was the Hui Taumata Mātauranga from 2001 - started in 2001 and went through to 2004.

A series of five hui that were held.

Tumu Te Heuheu was the organiser of it and some of the things that emerged there that were relevant to health as much as education, that the aim should be that our people, our young people, should be able to live as Māori, as citizens of the world, and should be able to enjoy good health and a high standard of living.

So that was an aspirational goal that came out of that.

The second one was the recognition that whānau are gateways to education, health, economy, society, and Māori potential.

In 2005, Te Puni Kōkiri's Māori Potential Framework emerged based around three pillars: whakamama, mātauranga, and rawa.

So into decade five.

Some of you will be getting closer to remembering these.

The - 2011, a really ground-breaking report, Ko Aotearoa Tēnei which is Wai 262 and it was about environmental protection recognising that unless we take steps to recognise it, and unless mātauranga can be applied to environmental science, then we won't be making much progress.

Also recognising that the environment was a key to health.

Then in 2011, Te Matapihi Housing hui was held.

Again, an important step of Māori taking a stronger interest in promoting their own approach to housing.

2016, Ihumātao was occupied for the first time.

I'm not sure whether it's been resolved or not but I've heard a rumour that it might have been resolved but I don’t think it's been officially announced.

2017, Whanganui River became a legal entity which was a major step in looking at it.

2018, there was protests against seabed mining in Taranaki.

In 2019, there was the Whakaari eruption.

I think Pania Newton stands out in that decade as a young leader who was moving her people, and all of us really, into a stronger position.

So the other thing in decade five was we begin to see that there is a shift in the system.

Tariana Turia put through in parliament the program now known as Whānau Ora.

The difference between Whānau Ora and other programs, that Whānau Ora was a combination of health, housing, social welfare, education.

As opposed to what we've been accustomed to, where you split all those things into separate piles.

So a really significant development.

Followed in 2014 by the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agencies, a new way of funding.

So that the accountability for Whānau Ora programs goes to the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agencies who don’t respond - they're not accountable to a department of the government.

They're accountable to the Minister of Whānau Ora.

So it's a different level of responsibility and it's one step away from state control.

2014, Pae Ora which you will hear about.

Mauri ora, individual health.

Whānau ora, health of whānau, and wai ora, the health of the environment.

Seen as three main pinnacles for Māori health into the future, now incorporated into the strategy.

In 2019, Wai 2575 was released with recommendations about health services and outcomes for health.

So this was just this decade just past.

You can see there are changes in the system that were beginning to emerge.

So here we are in decade six.

2020, Whakamaua: Māori Health Action Plan is released with the focus - shifting the focus of health away from health services entirely to having a much wider view of health and what it means and what action might mean.

2020, the COVID Māori response has been phenomenal really.

Every other pandemic we've had in this country, going way back to the 1800s and then into the flu epidemic of 1918, the smallpox epidemic, Māori death rates were three times higher than non-Māori rates.

The number of Māori who got illness was five times higher.

In the COVID response, the number of Māori people who have caught COVID is only seven per cent of the total who have COVID.

That was unexpected.

The expectation was that Māori would be severely affected by it.

The reason they weren't affected was that Māori took it into their own hands to protect their people.

So that one of the first public views of that was that - some of you might have been there - road blocks.

People saying you're not coming in here because we want to protect our whānau.

So they were very protective.

Trying to keep their own people safe and isolated.

Marae said if we're going to be helpful, we want to shut down the marae.

Our marae shut down on 19 March, which was actually before the lockdown.

Partly because there was some debate about it.

Some people said well you might want to use the marae as a place for people to have refuge.

The other view was that we can't guarantee the safety of our people, what we should do is lock it down.

So we locked that down.

Whānau support began to roll around right through the country.

Whānau Ora packages were delivered, particularly to older people, and we saw that a number of our own people began to take on new roles such as vaccination for other things and also testing for COVID.

2021, there's an announcement a Māori Health Authority will be established.

It's ongoing.

It's just getting off the ground.

Talk about it is just getting off.

2021, Oranga Tamariki begin to talk about a Māori Transition Authority.

So we're going to be well.

We'll have a lot of authorities.

Better watch out this year.

2021, one week ago from today, there was a group of unruly people walked through the streets of Fielding.

If you see that man at the front leading the haka, you're going to hear him talk tomorrow.

But that was a protest against excluding Māori wards when council have the opportunity to incorporate Māori wards into their routine.

So that's just a hint of what this decade might bring.

It's been quite a powerful start to a decade.

We might see how that proceeds.

But what I really wanted to talk about is the decades ahead and what will give shape to them.

How will they be shaped?

We can learn a lot from the past that we've already seen.

But we know that the future will be different.

Our population will be close to a million.

It's now getting towards 800,000.

If you add to that all the people in Australia who are working in the mines and other things, the population would be over a million.

Our people will live longer.

Māori life expectancy for men and women is increasing and the rate of increase of life expectancy for Māori is greater than the rate of increase for non-Māori.

That's because when you get sort of above 90, you slow down the rate of increase.

But our life expectancy is getting longer.

So in the future, we can expect to have more older people.

We know that whānau will be dispersed across Aotearoa and the globe.

They won't be living in one place; they'll be all around the world.

We know that we will have digital communication as part and parcel of life and that our tangi might be Zoomed.

Our births, twenty first birthdays, weddings, we might attend them digitally.

We know that our water, our land, our air are going to exposed to multiple threats that we haven’t even contemplated.

We're beginning to see them now.

Global warming and an overpopulated world can spell disaster.

We're going to have more pandemics.

COVID was just a test.

There's going to be more pandemics and other catastrophes.

We're going to have to shift the focus from late intervention to early intervention and prevention.

We can do much better there.

There'll be new technologies that will affect the way we work, the way we learn, and the healing that we do.

Marae will feel the dual pressure of encroachment and cultural diffusion.

On the positive side, we will have many more well qualified Māori to cope with the changing world.

Talking about the medical profession for example, there's now something like 400, close to half - 400 or 500 Māori doctors.

Unthinkable three or four generations ago.

We'll see our rangatahi grow into confident leaders and we've seen some of that already today.

As we saw during COVID-19 pandemic, we will continue our proud tradition of responding to change in a decisive way.

We won't be told to do it; we will want to do it.

We will build on the foundations that we have already laid over the last 50 years so that we can be well prepared for future challenges.

These are the foundations that we can pick up for the last 50 year, whenua, land.

It's a foundation for health.

Te taiao, our environment, a major foundation for health.

Whānau and whanaungatanga.

Mātauranga.

Raukaha, our capability, our workforce.

Te hononga, the way we collaborate rather than stay in silos.

Hautūtanga, our leadership.

Te ao whānui, looking at the global perspective.

Te Tiri o Waitangi and its relevance to the future.

Rangatiratanga, self-determination.

I'm just going to talk about those 10 things because they are the foundations that we can pick up from those five decades I talked about.

Foundation that are going to be relevant to being healthy in the future.

So the first one then is whenua.

Would we be called tangata whenua if we had no whenua?

We've got a bit of a problem there.

Land is more than an asset.

Land grounds us.

Land leads us.

Land feeds us.

Land connects us.

Land is the foundation for our homes and land defines us.

The task in the future will be to protect the land and in so doing, Māori will be able to live well as tangata whenua.

So land is critical for health.

A task for the future is how we can protect our land.

That's what Dame Whina Cooper was doing in her time, the 1970s, was not one acre more.

Not just having land mass but having land that is safe and secure and contributes to us.

The other foundation is te taiao, the wider environment.

We've got to stop destroying land.

Stop ruining waterways and forest and the air.

We've got to stop KiwiRail from putting great big hubs on rural land.

Perhaps we should have Kaitiaki appointed to protect the environment.

They would have the authority themselves to impose environmental ventures, including those in-built environments.

Anything that's a threat to Māori health and wellbeing.

When I'm talking about environment, we're talking not only about the natural environment but also the built environments in which we live.

The streets that we live on, the houses that we live in.

Every time we assess someone's health, we should also be assessing the environment that they live in.

Because that's where the answer may - will often lie.

Third foundation is whānau.

Critical.

Whānau are at the beginning, birth, and at the end, death.

Whānau link us to the past and steer us towards the future.

It's the intergenerational aspect of it.

Whānau alleviate pain and generate hope.

Whānau are the gateways to marae, te reo, and to te ao Māori.

Whānau autonomy will be a starting point for rangatiratanga and will be reflected in the ways whānau assume leadership roles in a changing society.

So that's putting a lot on whānau but that's really the basis for change.

Increasingly, whānau health will reflect ready access to housing, health, education, and social services.

But perhaps more importantly, it should reflect whānau autonomy and a whānau commitment to live well.

The fourth foundation, he kete mātauranga is about mātauranga Māori.

Māori models for health and wellbeing, we've seen these develop over the last three or four decades.

Te reo Māori and kaupapa Māori health initiatives will enable Māori to be Māori even when circumstances change.

The fifth one, raukaha, is about having a workforce that has the capacity and the capability to make a difference.

We want our workforce to be part of the community, not isolated from the community, to be well versed in te ao Māori, and to span the whole health domain so that it includes professionals, support workers, people with lived experience, all part of the leadership for health.

The sixth one, te hononga, recognises that splitting things into sectors or into disciplines really goes right against the world that we actually live.

We need a holistic approach that brings together health, education, housing, employment, welfare, and the economy in order to align with the realities where Māori live.

We've got to get better at doing that.

But a health program by itself will not necessarily generate the best health that we could have.

We've got to have some way of pulling them together.

Collective action, we need to have action that goes across disciplines and across sectors.

So that will endorse Māori world views and strengthening resolve.

This is something that is really needed.

Difficult to do in Wellington.

But it may not be so difficult to do in our community.

The seventh one, te toa takitini is about leadership.

We want leadership that's collective and distributed.

We don’t want it all in one place.

We want it to be distributed and working together.

Our leadership will be evident in communities, hospitals, and in all health professions.

It will be supported by iwi.

It will be evident on marae.

Our leadership will recognise Māori community priorities, not our own priorities, but the communities of our people, and will ensure access to quality care.

Our leaders in health will be part of a wider Māori leadership team to take us into the future.

The wider leadership team will be people who have got skills in other areas but the collective nature of that will be important for the future.

Foundation eight, te ao whānui is about the world that we live in.

Māori will be global citizens.

Increasingly that’s the case and it's likely to continue.

We should still be able to be Māori even when living in other countries.

That's a challenge but with digital communication and other things, that should be possible.

But we also want to be part of a global Indigenous network.

We want to be represented on international forums, Indigenous governance, worldwide health forums, sporting, academic initiatives, and trade and economic ventures.

So that our future means us making greater contact with the globe and the world outside us.

Foundation nine, Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

It will continue - the treaty will continue to be part of all environmental, social, and economic legislation and policies.

Up until 1984, the treaty was seldom mentioned in education or in health or in those other social policies.

Māori will experience genuine partnership and full participation in all aspects of society.

The Māori Health Authority will join other authorities to gain consistency and impact across health, education, housing, employment, and social wellbeing.

In other words, the Māori Health Authority will be part of a network of groups rather than standing alone as the only contributor.

Foundation 10, rangatiratanga.

Māori decision making will be evident in communities, regions, and nationally.

That will make it possible to live as Māori.

Predictably there'll be many Māori authorities built on the foundations laid by marae, by iwi, by Māori commissioning agencies, by kaupapa Māori systems, and by Māori community agencies.

A Māori Health Authority will have a national role.

So there are already authorities around.

The danger will be to isolate them into little bits.

Māori authorities will not necessarily mimic state systems.

So we wouldn’t want, for example, the Māori Health Authority to mimic the wider health service.

Nor will they be fragmented by sectoral approaches.

Instead, they will adopt kaupapa Māori values to ensure that Māori can flourish into the future.

So that's the 10 foundations that we pick up from the last 50 years, the last five decades, that will have some importance for health into the future.

The land, the environment, our whānau, mātauranga, our leadership, a comprehensive capability, and integration which will be the hard bit I think to do.

But also being part of the globe, recognise the significance of the treaty, and having self-determination.

I haven’t finished yet.

So this is a question.

Should we be ready to respond to a changing world?

We know the world is changing, should we be ready to respond to that?

Or should we create the future we want?

So do we wait to say things are changing, we better change.

Or do we say we want to be ourselves?

We want to be well into the future.

What is it that we want?

How are we going to do it?

So the future we want, let's build on the foundations that have been laid over the past five decades and then let's have some focused planning for the future.

I understand that's what likely to happen at this hui later today and tomorrow, integrated planning for the future.

Building on our foundations.

When we do the plans, we then have to put them into action so that we can actually create our future and that, we hope, will lead us to mauri ora.

So thank you for the opportunity to be here.

My apologies, I'm going to have to leave at one o'clock.

But really just to reiterate that there is no future without a past and that we should build on what we've got.

The good news is we're not starting from scratch.

If we'd been having this meeting in 1970, we would have been unsure exactly where we want to go.

We're clearer now what this decade is going to look like and the next one behind it.

But we need to be thinking about what is it that we want as we move into the future?

Rather than what does the future - how is the future going to dictate change to us.

Then finally, in case you've forgotten, these are the foundations that will shape our health in the future.

Whenua grounds us.

Te taiao protects us.

Whānau nurture us.

Mātauranga defines us.

Raukaha helps us.

Te hononga unites us.

Haututanga guides us.

Te ao whānui extends us.

Te tiriti guarantees us.

Rangatiratanga asserts us.

Kia ora.

[Applause]

Nō te Matau-a-Māui ahau.

Ko te Whanga-nui-a-tara ika.

Te Kaenga o tōku whānau.

Ko Ngāti Kōtimana.

Ko Ngāti Ingarangi ōku iwi.

Ko Ashley Bloomfield tōku ingoa.

Ko te tumu whakarae mō te hauora e ngā kaihoe o te waka hauora.

Tēnā koutou katoa.

Kia ora whānau, it’s great to be here and the reason I can stay and be a bit flexible with the time is I don’t have to do a one o’clock stand-up today.

The Minister is flying solo on that one because there are some budget political announcements so I will give you a sneak preview.

Kia ora koutou katoa.

There are five new cases of COVID-19 in New Zealand today.

They are all in managed isolation.

Then, of course, after I’ve perhaps shared a few thoughts, yes, I will have some time for questions and look forward to that.

Just for those of you who haven’t watched one of the media stand-ups for a while, just a reminder of how the question time goes.

You don’t put your hand up in the air and wait to be asked.

You just shout your question at me.

Go, Dr Bloomfield, Dr Bloomfield and if someone else is already shouting their question, don’t let that put you off.

Just shout louder and if someone has already asked the question you wanted to ask, just feel free to ask it again but I’m just letting you know, I will give you the same answer.

It’s been quite a year, hasn’t it? A year of challenges and the challenge is ongoing.

A lot of the interviews and talks I’m doing at the moment, I’m just reminding people that every day and night, 24-seven, there is a large number of people who are protecting all of New Zealand from this virus that we need to keep out and it’s not easy.

It is a tricky virus and it is an unpredictable virus.

We have seen even just in the last few weeks, if we look at countries like Singapore and Fiji and jurisdictions like Taiwan that has been held up as the poster child for its COVID-19 response, it doesn’t take much for this virus to find a way through the border.

It’s sneaky and then you have quite a challenge on your hands.

So we must not forget and underestimate the work that is going on every day to keep New Zealanders safe from the virus.

In that context, the fact that we are rolling out a vaccine program, the biggest one ever, while we keep a pandemic at bay and that our intention and aspiration is to vaccinate all eligible New Zealanders - that includes all of you so yes, thank you for taking up the invitation as the opportunity arises during the year.

So we want to vaccinate all eligible New Zealanders before the end of the year because that’s the next very important thing we can do to keep New Zealanders safe.

I’ve done a few talks recently just reflecting on what I call lessons on life in leadership from COVID-19 in 2020.

I think some of them are really relevant to this hui today and the series of Hui Whakaoranga.

One of the key lessons for me goes back to the announcement about the lockdown on 23 March when the Prime Minister stood up and said on live television - or she might have been sitting down, actually, in her office and she said I introduced the alert level framework to you two days ago and I said we were in alert level 2.

I said we would be in alert level 2 for a couple of weeks.

Well, we’ve changed our minds.

Today we’re going into alert level 3 and in two days’ time, on Wednesday 25 March, New Zealand Aotearoa is going into alert level 4.

Here’s the interesting thing.

No one said, why? Everybody got it and in fact you could almost feel the collective sigh of relief.

The reason for that was we had - and you might - some might argue uncharacteristically for the public sector, right from 27 January, we had kept the public fully informed in an open and transparent way and we had built their trust that when it came to the point of asking them to do something quite extraordinary, that none of us envisaged - it wasn’t in our pandemic plan.

It certainly was nothing that any of us envisaged would happen in our lifetime but when the Prime Minister said, what that means is we need you to stay home for several weeks, people said okay, we get it.

We understand why.

What do you want us to do? Here was this wonderful communication that was the strapline, really for - it was a call to action.

Stay home, save lives, be kind.

It’s a very different message from stay home and look after yourselves.

So New Zealanders embraced that and in fact many communities had already embraced that.

Iwi Māori were the first to do this because right at the top of their - the forefront of their minds was the pandemic 100 years ago and how their whakapapa had been compromised by that pandemic.

They did not want that to happen again.

So they had mobilised - they had seen the risk and the danger early.

They had mobilised and yes, the media focussed on some aspects of that mobilisation.

The roadblocks, as they love to call them, but actually, that was just part of the mobilisation of iwi to protect their kuia and their kaumatua.

To protect their whakapapa.

That was, in a sense, an inspiration, I guess, for the rest of New Zealand and we saw then when the call to action was offered by the Prime Minister, people responded.

Individuals responded.

Whānau responded.

Communities responded.

So instead of staying home and looking after themselves, even in their bubbles they thought about what can I do for others? The greatest thing that people did was, they stayed home so that whilst we set out at the beginning of that lockdown period to - we hoped, to stop the rise and to suppress the number of COVID infections, it became apparent as time went by that we had the opportunity to get rid of COVID in our country and that’s what happened.

From that, then was born a whole new approach.

A whole new strategy.

An elimination strategy.

The reason for it was that people heard the call to action and they did what needed to be done.

The reason that they did what needed to be done, because they understood why.

It’s a great leadership lesson.

We spend a lot of time explaining to our people the what and the how.

Actually, our staff at the Ministry and across the public sector and across New Zealand, people and communities knew what needed to be done and they just got on and did it because they understood why.

Here’s the opportunity for this next phase of hauora Māori in Aotearoa and with the blueprint that is there, that is part of it, throughout the five year Whakamaua plan is to think not so much about the how and the what but the why.

If people understand why - and that is not just Māori but if non-Māori and the wider health system understand why, then they will know what to do.

They will see what needs to be done and they will do it.

So it’s the opportunity to develop and articulate clearly and consistently the vision, the why, over five and 10 and 20 and 25, 30 years that will take us there.

I had a quick look through Sir Mason Durie’s slides from yesterday and I’m sorry I didn’t get to hear him speak.

It’s always a treat and he’s someone who is influential in the development of my career, I worked closely with him when he was Chair of the National Health Committee and I headed the secretariat.

But it looked like a wonderful - typically Mason, historical journey looking back to understand then where we need to go next.

I’m looking forward to, and I’ll watch the video of his presentation.

I hear that’s available.

So a great lesson in life and leadership.

If people understand why, they will do extraordinary things.

The best definition of leadership, the one I use, is that leadership is an invitation to collective action.

Last year, we saw that if you extend that invitation and people understand why, they will do extraordinary things.

So here’s the opportunity not just for Māori health but for Māori wider wellbeing and the wellbeing of our nation.

What if we turned our collective actions and our collective inspiration to addressing some of those other issues that we aspire - must aspire to and must do better on.

Child poverty.

Homelessness.

Affordable housing.

Environmental sustainability and, indeed, our global leadership role along with others to address climate change.

No one is coming.

As I often say to my team, no one is coming.

It’s up to us.

Actually, at the moment they can’t come anyway because we’ve shut the border so - but we have everything we need.

We have everything we need and everything we are going to get.

So we should get to it.

One of the second lessons for me from last year was around the need and to constantly be reviewing and learning and adapting our response.

Again, if I reflect on the last 25 years or so that I’ve been in public health and I’ve had an interest right from my early days with the National Health Committee on inequity and the determinants of health and the impacts they have on people’s wellbeing and on how to address inequalities in health, particularly those that are unfair - in other words, inequities.

We have made progress and the opportunity is for us to make even greater progress and at much more pace but there is a lot to learn.

A good example here is even if we look at something like our current childhood vaccination rates which have dropped overall in the last couple of years but particularly for Māori.

But that’s not the end of the story because the other part of the story - and this is why we must look at the data all the time, is that in some rohe around the country, it hasn’t dropped and vaccination rates for Māori are the same as they are for non-Māori in other areas.

Te Tai Tokerau is a good example.

They have dropped quite a lot more.

There is a 10 point difference between Māori and non-Māori but there is even in that comparison, there is a guide to what can be done to address that inequality that could turn into an inequity.

So we must keep reviewing, keep learning and remain open to changing and responding and we’ve had to do quite a bit of that over the last year.

The one o’clock stand-ups, which some of you will remember started off as a small thing and got bigger and bigger, especially through the lockdown period when it was apparently compulsory viewing.

There was a joke that the best time to go to the supermarket was at one o’clock because everyone was watching TV to find out what the instructions were for the next day.

But over time, as the response went on, those one o’clock stand-ups became something like a performance review on live television for me every day when reporters would have the latest tip off about someone who didn’t have the PPE they needed or something that hadn’t gone right somewhere.

Our response was to say, yes, that doesn’t sound right.

Actually, we’ll look into that, we’ll fix that or we haven’t got that information but we will find it for you or simply, we don’t know.

Or here’s another one, it’s a challenge for leaders, we’ve changed our mind.

The evidence has changed.

The interesting thing, when I talk to New Zealanders and many of them write to me or email me or come up to me on the street and ask for selfies - I’ve only done five so far here this morning.

But they want to have a chat, but a common theme is the reason they trusted the response was because we didn’t pretend to have all the answers.

It was because we said right from the start, here’s what we know and if we didn’t know, we would say we don’t know.

We wouldn’t try and fudge it.

If something hadn’t gone right, we would say yeah, that’s - I’ll take responsibility for that and we’ll sort it out.

I talk about this as leading with humility.

It’s been - it was a lesson.

A big lesson for me last year as a really core value around leadership and leading with humility is characterised by leaders who will listen to advice.

They will be prepared to say they don’t know.

They will be prepared to say when they got it wrong and own that and they will be prepared to change their minds if something else comes along.

Of course, the opposite of leading with humility is the other H-U word.

Hubris.

We’ve seen around the world where some leaders have led with hubris rather than humility and the impact that has on their responses to COVID-19 and I daresay in any situation.

So I guess that just leads into the final comment I would make about the values that have underpinned my leadership and I think they actually are very strong overlay with our values we have as an organisation and what is underpinning our own ongoing growth and development as a treaty response of organisation, the Ministry of Health and the leadership role we have to the wider system in doing that.

So the values that I’ve really reflected on over the last year, which have been important because in a global pandemic, you cannot control the context.

There’s a lot that is outside your control.

In fact, just about everything.

So when you’re in that situation I’ve reflected on where there’s not much inside your control or within your control, the one thing you can always control is how you behave, how you respond, and how you come across.

It’s one of the first things you learn as a leader, people won’t remember so much what you said and did, they’ll remember how you made them feel.

Even if I didn’t know the answers to lots of questions and even as I responded to questions being fired at me by the media and sometimes the same question more than once, just being calm was actually what - I can tell you, it’s what children remembered because they wrote to me and said thank you for being calm.

Even if I didn’t feel calm.

So responding in a values based way because our behaviours reflect our values.

It’s really important.

So I’ve talked about kindness.

I’m a - hand up here, I’m a fully paid-up member of the Kindness Club.

I have been for some time and it doesn’t - it shouldn’t take a pandemic for us to be kind to each other, actually.

Humility I’ve talked about.

Integrity is another thing.

Doing what you say you will do and the other thing is compassion.

Even in the midst of a huge significant situation, responding to the pandemic, every one of those cases is a person who is unwell and a whānau that is worried and anxious.

Every one of those 26 deaths was a whānau that was grieving because they’d lost a loved one.

So we must always underpin everything we do with compassion and of course kindness extends to be being kind to ourself.

You can’t be kind to others unless you’re being kind to yourself.

Looking after your own mental and physical wellbeing, so I’ve talked a bit about that.

So one of the things I’ve been doing over the last year as well is just - well the last six months is recognising that the importance of speaking out about personal wellbeing is almost an obligation of senior leaders because it’s very empowering for junior leaders.

Many of them aspire to be senior leaders but they think because they get anxious or they have self-doubt or because they get stressed or because they run up against the boundaries of their resilience, that they cannot be a future leader.

Hey, welcome to the club.

If you find a leader who doesn’t have self-doubt - it’s my advice to them, if you find a leader who doesn’t have self-doubt or get anxious, don’t work for them because you won’t learn anything.

They won’t teach you and they won’t listen.

So, we’re going to have to do a lot of listening as we embark on the next phase of this journey.

The health system reforms, which you will all be aware of and a lot of the discussion today has been about the structural changes that are intended to be made, including the establishment of a Māori health authority.

I’m excited about that as a means to an end, not an end in and of itself.

All the structural reforms will be for nothing if we don’t change the way people behave and act in the sector.

That’s where I think Whakamaua has got a really important role to play.

Inside that are a number of actions and strategies that are designed to help shift the way the system thinks about Māori health and how it responds.

The structural changes can help that but they are only a means to an end and we need to all be united in our work as organisations, not just leaving it to the Māori Health Authority.

We have an ongoing deep responsibility as the sector stewards, kaitiaki, to help shift the way the system behaves, the individuals within it and the organisations within it and indeed the system to improve Māori health.

So, I might just leave it there and I’ll look forward to receiving your questions.

Kia ora tātou.

Additional videos from our other Hui Whakaoranga 2021 key speakers will be added to this resources page over time.

Insights documents

Insights documents were developed to spark discussion and complement keynote speeches at Hui Whakaoranga. A brief summary of these documents and a PDF download link are available below.

"Scoping the past to reach the future – A personal account” by our keynote speaker Tā Mason Durie provides intriguing personal insights covering the last five decades of Māori Health reform, and how this informs our pathway forward.

An extract, “Foundations for Tomorrow”, was developed from Tā Mason Durie’s “Scoping the past to reach the future – A personal account”. In this document, Tā Mason provides ten foundations to the future of Māori health, drawn from his experience with Māori health reform over the past five decades.

Prior to Hui Whakaoranga 2021, rangatahi Māori insights and aspirations for the future of Māori health were gathered through interviews with rangatahi with different roles and experiences of pae ora. Their whakaaro is captured in the rangatahi insights report below.

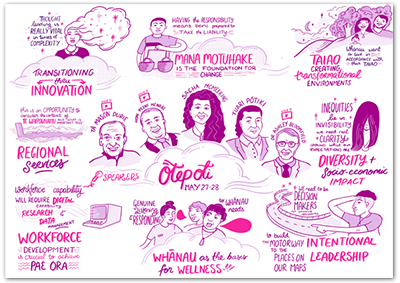

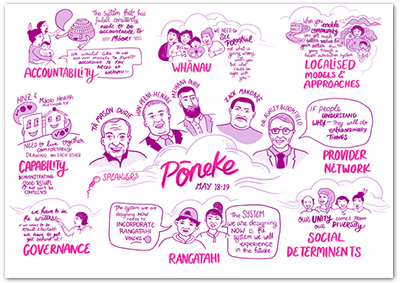

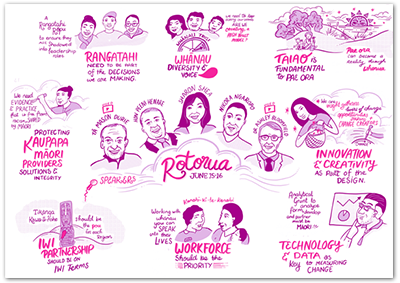

Illustrations

A series of illustrations captured the key themes from each of the regional hui.

Regional illustrations

If you have any questions about Hui Whakaoranga 2021, please reference these FAQs.